In these days the museums of Rome will reopen and it will therefore be possible to visit some exhibitions organized to enhance some historical events that have concerned the city, like the one organized at the Trajan’s Markets “Napoleon and the myth of Rome”.

Set up on the occasion of the bicentenary of the emperor’s death, the exhibition celebrates him by highlighting the relationship between the French emperor, the legacy of the ancient world and Rome.

The apotheosis of Napoleon’s imperial dream

Rome represented the apotheosis of Napoleon’s imperial dream: following the occupation of the city by the French army and the exile of the Pope it was declared, immediately after Paris, the second city of the Napoleonic empire and waited for five years, preparing for the event, the arrival of the emperor.

Napoleon’s intent was therefore to give new shine to Rome at a time when the great glories of the Baroque were behind and the city was in decline (we are in the period of the “Marquis Del Grillo” – a famous Italian TV drama that perfectly describes this era), creating a new imperial city.

Many projects were conceived and partially also realized for this purpose, for the recovery of the “ancient” and therefore of monuments, temples, statues and triumphal arches which at the time were almost completely buried, with the aim of creating a sort of an archaeological park including also a public promenade to make the area of ancient Rome pleasantly accessible to everybody.

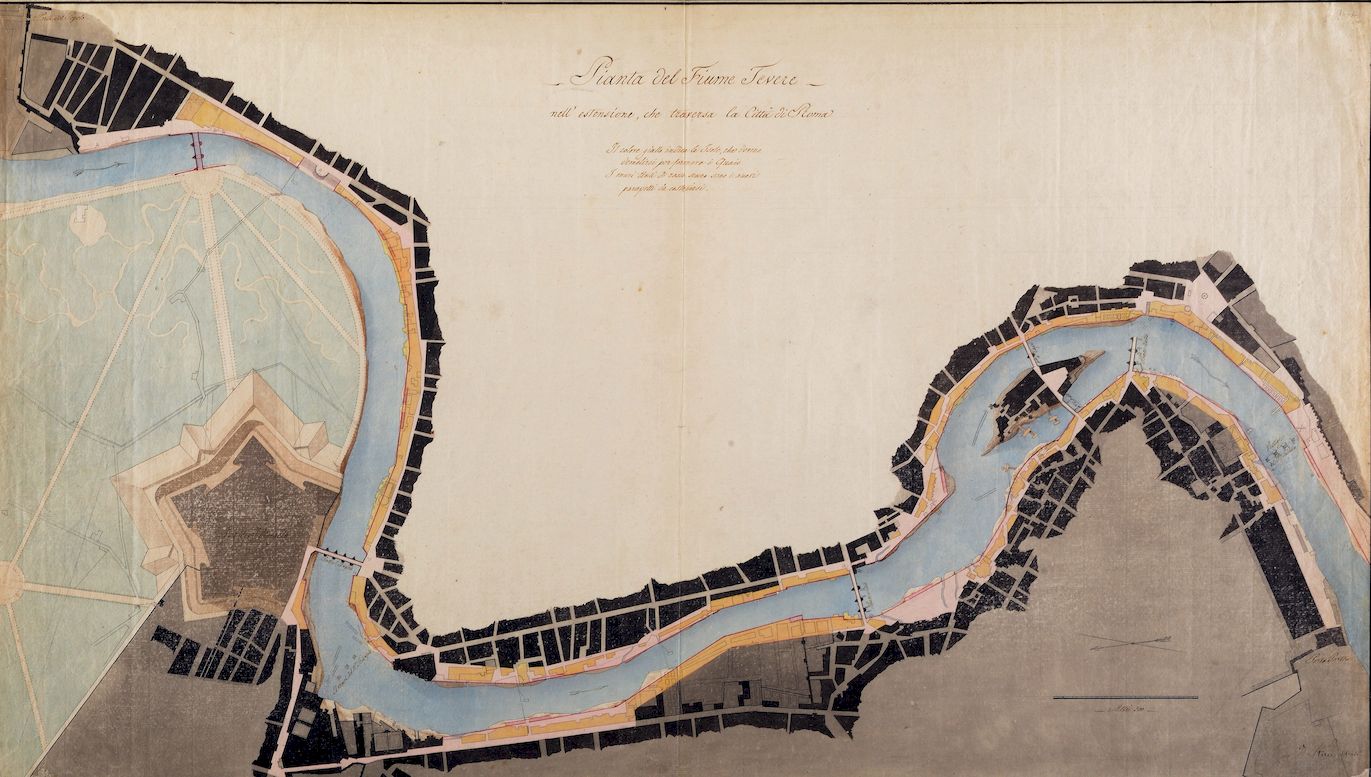

Also on the urban level, other interventions were planned to renovate some areas of the city such as the Pincio, Piazza del Popolo and the Flaminia’s area with a public promenade between Porta del Popolo and Ponte Milvio (never built), and also the Pantheon area and the arrangement of the banks of the Tiber, projects to be carried out involving important Roman (Camporese, Valadier and Stern) and French (Berthault and Gisors) architects.

Even the Quirinal Palace was transformed to accommodate the emperor who, however, unlike some members of his family who stayed in Rome, will not be able to see the city and will never arrive.

Following Napoleon’s traces in Rome

There are many other evident traces of Napoleon’s relationship with Rome.

Palazzo Bonaparte, which overlooks Piazza Venezia, with its green balcony, festooned frescoed walls and lowered windows from which Madame Mère, Maria Letizia Ramolino, Napoleon’s mother, at the age of eighty, observed the come and go of carriages along via del Corso and piazza Venezia.

The Napoleonic Museum which tells the story of the Bonaparte family that has always been linked to Rome and strongly rooted in the historical context of the city.

The Borghese Gallery, where we find the famous statue representing Paolina Bonaparte Borghese, Napoleon’s sister, represented as a Greek goddess, the winning Venus, commissioned to Canova by her husband Camillo Borghese on the occasion of her wedding.

From the Rome of the Popes to a more modern Rome

An important example of the Napoleonic legacy is the introduction of the idea of “public asset”, meaning accessible to all and not just to nobles or cardinals, and its preservation.

Napoleon contributed to the transition from the Rome of the Popes to a more modern Rome, combining the principles of the Age of the Enlightenment, characteristic of his era, with the exaltation of the past and the ancient in respect of the tradition and history of the capital.